By Timothy A. Schuler, LAM Staff

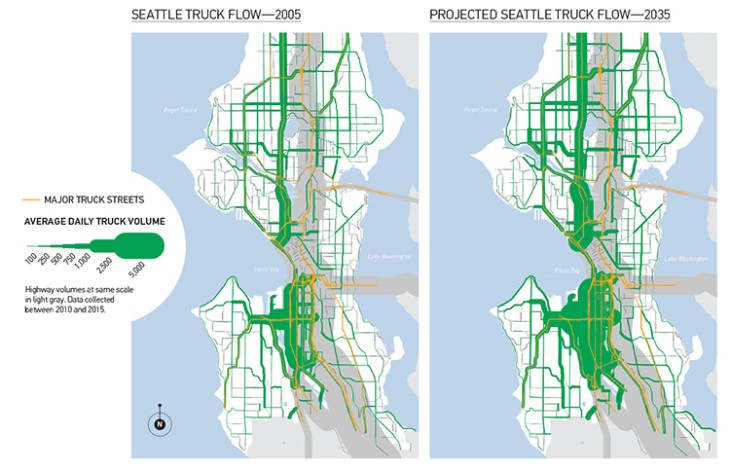

The sight of a bike lane blocked by a delivery truck is so common that it has birthed Tumblrs and Twitter hashtags, often as a way to either shame drivers or encourage city officials to better enforce traffic laws. What those Twitter users may not have considered is that every box from Amazon or Blue Apron requires a trip from a warehouse to their door. And as online sales continue to grow (by roughly 15 percent per year), the increasing volume and frequency of home deliveries has cities like Seattle searching for solutions. “For us, it means curb use is changing, and it’s changing fast,” says Christopher Eaves, a civil engineer with Seattle’s Department of Transportation.

The increase in deliveries has major implications for Complete Streets programs, which seek to accommodate the needs of pedestrians, bicyclists, transit riders, and vehicular traffic within existing corridors. Like many cities, Seattle has a Complete Streets ordinance, adopted in 2007. At the same time, the city is working to expand its urban canopy and curbside green stormwater infrastructure. “So there’s a whole lot of things competing,” says Peg Staeheli, FASLA, a principal at MIG | SVR in Seattle who thought a lot about freight during her time on Seattle’s Urban Forestry Commission.

Recently, the City of Seattle partnered with the University of Washington (UW) and several major retailers to launch the Urban Freight Lab, a three-year research effort to better understand the rapidly changing landscape of goods delivery. Until now, cities have not viewed goods delivery as a system that needs to be designed, says Anne Goodchild, a professor of civil and environmental engineering and the director of UW’s Supply Chain Transportation and Logistics Center. What exists today, she says, is akin to a bus system without bus stops.

Part of the reason for this fragmentation is the industry’s multifaceted nature. Unlike public transit, goods delivery has no single governing body or regulatory agency. Many of the carriers are private companies that deliver goods sold by other private companies to privately owned buildings. As a result, municipal governments often lack reliable data on where loading bays and loading zones are located, and whether or not they are meeting demand. To establish that baseline in Seattle, the UW team mapped the location of every existing loading bay and zone in downtown Seattle. They found that 87 percent of buildings have no alternative to curbside parking for freight delivery. When a spot is unavailable, many drivers double-park. They risk getting tickets, but as CityLab reported in April, many carriers treat traffic fines as part of the cost of doing business.

As companies like UPS test their own solutions, experimenting with bicycle and drone delivery, Goodchild’s team is working to identify where curb access might need to be reallocated. They also are developing Freight Score, a ranking akin to WalkScore but for freight accessibility. Other ideas include adding locker systems to high-traffic areas such as transit hubs. (In France, 20 percent of parcels already are delivered to automated lockers.) Goodchild’s job is not to “make freight a priority,” she says. “My job is to use the expertise that I have to help develop livable places that people enjoy.” The question, she says, is, “How much do we ask the transport to modify itself for the place? And how much do we modify the place for the transport?”

It’s a question Staeheli thinks landscape architects can help answer. They can aid cities in understanding the effect goods delivery has on people and habitat. “I think this is a really important conversation that we need to have,” she says. Barbara Ivanov, the director of the Urban Freight Lab, says the first thing designers need to do is recognize that goods delivery has become as essential as water or electricity. “If you don’t believe that,” she says, “it’s just not going to work.”